- On-Call News

- Posts

- The Double-Speculum Dilemma

The Double-Speculum Dilemma

What’s the point of the exam if the speciality will just repeat it?

Contents (reading time: 7 minutes)

The Double-Speculum Dilemma

Weekly Prescription

The Gospel According to the Handover Sheet

Board Round

Referrals

Weekly Poll

Stat Note

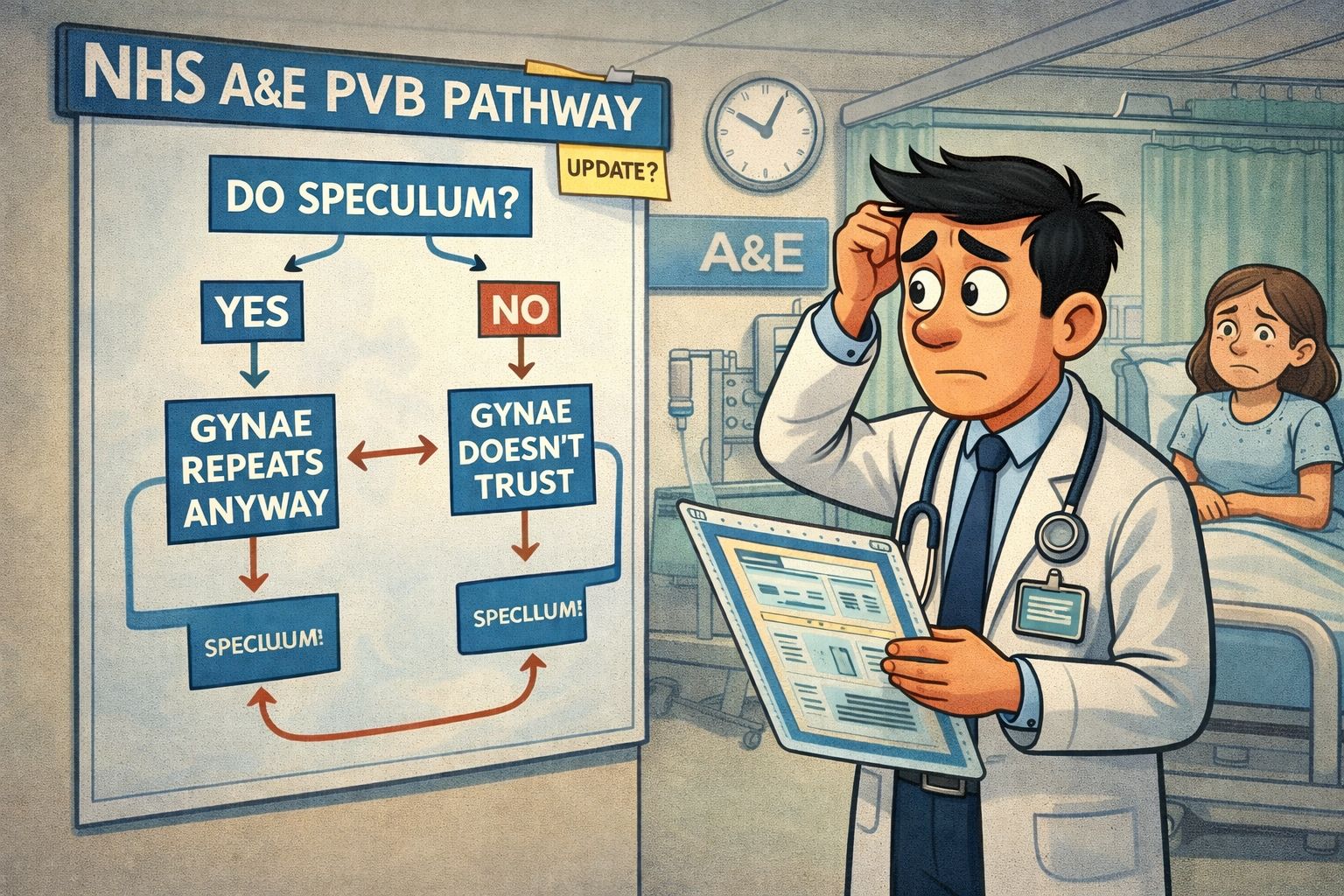

The Double-Speculum Dilemma

What’s the point of the exam if the speciality will just repeat it?

Every single day within the NHS, turf war questions surrounding the conduction of an invasive procedure take place. The argument goes as follows: “Why should I do an invasive procedure if the specialist is going to repeat it anyway?” It’s a question we have all heard and touches on not only the patient experience, but the very idea of a ‘generalist’ vs ‘specialist’.

Much like in most debates, the point is often best demonstrated through imagery. We will paint such a picture by looking at the patient who presents to the emergency department with Per Vaginal Bleeding (PVB). Hospitals will vary in their approach to such a patient, with many trusts deploying PVB protocols to streamline referrals. Others may rely on the conventional method of A+E doctor assessment before referral to a speciality or direct referral from the A&E triage nurses.

The Argument for Omission

If an EM doctor does see the patient first, however, the decision to undertake a speculum exam seems to have become layered with different approaches. The argument from Omission, which is often framed as the ‘merciful’ approach, abstains from the undertaking of a speculum exam, seeing the role of emergency medicine as a service that ‘triages and stabilises’. Recognising the invasive, physically uncomfortable nature of the exam leads these doctors to believe that violating a patient’s comfort twice is not delivering an appropriate level of care.

The EM doctor recognises that a gynaecologist performs several speculums every single day and will be able to identify a subtle cervical pathology that an EM doc may miss. They won’t trust our findings anyway. Why should I put my patient through this experience again, and also not make the best use of my time in a crowded A&E department?

The Argument for Performance

Is it ever possible for this hypothetical EM doctor to triage our patient effectively with an incomplete picture of their presentation? Yes, evidence of bleeding could be a minor miscarriage, but it may also show retained products of conception in the cervix or rather, no bleeding from the vaginal canal at all. To be a proponent of such an argument is to acknowledge that the job of the EM doctor is to prefer referring symptoms rather than a differential diagnosis.

A moment’s reflection will allow us to ask an important question: Why is it that gynaecology ends up repeating the exam? Well, it is likely either due to an incorrect or a poor referral, leading to the speciality losing trust in the data they are given. So, they proceed to repeat the exam for their own medico-legal safety.

But surely all of the On-Call community can see how easily such a set of events could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. If EM doctors know gynae will repeat it, they will stop doing it. Because they have stopped doing it, they lose the skill of accurately interpreting a speculum examination. Now that they have lost the skill, their referrals will become worse, and to finish off the cycle, because of their worse referrals, gynaecologists will choose to repeat the exam even more frequently.

Someone Bring Some Nuance

Maybe these blanket ‘rules’ need more nuance. A patient who is haemodynamically unstable and receiving resuscitation can’t wait until the gynaecology registrar is out of theatre; they need to have a speculum examination there and then to localise a source of bleeding. This differs from your stable patient with minor spotting, where sparing the patient of two exams is empathic.

As we all know, however, with this attempt at nuanced logic and rule-making, the difficulties will always arise within the ‘grey areas’ of medicine. What is classed as ‘urgent’ by some may not be viewed the same way by others.

Is the ‘American Dream’ Killing the US Surgeon?

To be a surgeon is not simple, and nor should it be. You would do well to find another career that carries the same immediate and long-term risks, requires the same technical skills, and demands the same emotional fortitude. The journey to becoming a consultant surgeon is a tumultuous and rocky one, but one that, for many, is worth the struggle.

Attention was drawn however, to a paper published in JAMA Surgery last week which highlighted that US surgeons face a higher risk of death from various causes, including cancer. The cancer-related mortality rate for US surgeons was 193.2 per 100,000 people, which is nearly double the 87.5 figure seen in non-surgeon US doctors. Yes, overall death rates amongst surgeons remain lower than those of non-doctors in other professions, but the high cancer rates compared to other doctors have many questioning the explanation.

The Surgery publication put this down to the demands of surgical practice, which include long work hours, high-pressure environments and occupational exposure through radiation. Do you think these results would translate to the UK? US doctor work culture is significantly different, with many residents routinely clocking in over 80-hour workweeks. Compile this with a culture built on litigation concerns and defensive medicine, and it builds a different landscape for our US colleagues.

Perhaps this could serve as a sobering reminder that whilst ‘surgical life’ demands a lot from us, the NHS (for all its faults) might just be saving us from the severe outcomes we are seeing across the pond.

Applying to Specialty Training?

Get expert help with FREE webinars from Medset…

Public Health ST1 - Jan 12th

Rheumatology ST4 - Jan 13th

Obs & Gynae ST1 - Jan 13th

Gastroenterology ST4 - Jan 14th

Respiratory ST4 - Jan 15th

Paediatrics ST1 - Jan 15th

Radiology ST1 - Jan 19th

Getting an interview can be hard enough – so once you’re there you need to give yourself the very best chance of success.

Medset’s expert Courses and Mock Interviews are delivered by previous top-performers who’ve aced their applications and interviews.

They’re more than just practice scenarios, you’ll learn the frameworks that will allow you to maximise your performance and get the job you want.

CT/ST1 | ST3/4 |

Looking for Professional Development Courses?

Expert delivered training, on-demand, virtual classroom or in-person.

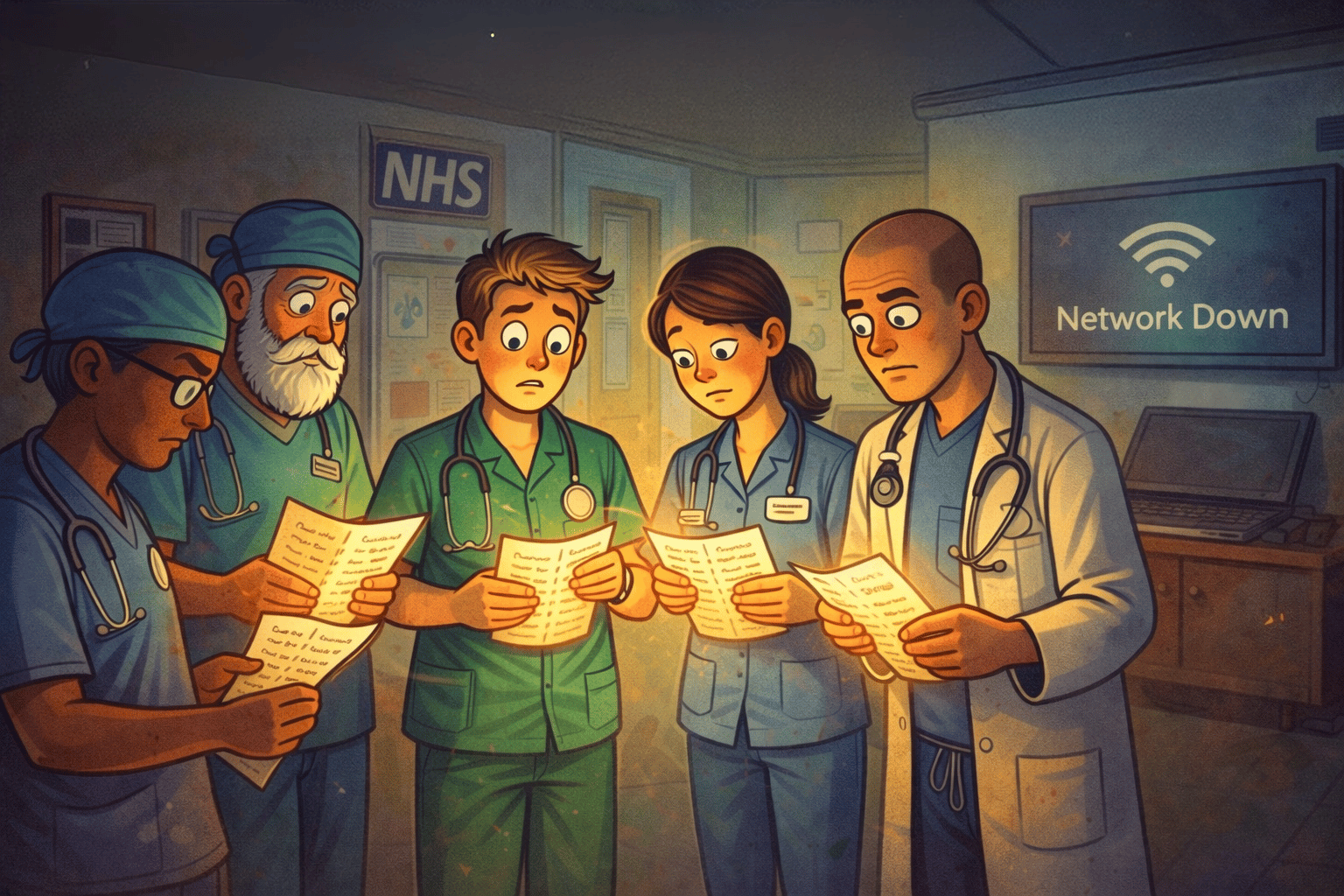

The Gospel According to the Handover Sheet

The surprising power of the folded A4 sheet

When we think of our profession, there are some constants that come to mind, no matter where in the country we work. The humble handover sheet is one of them. They may come in all formats, font sizes, column titles, and page orientations, but you can be sure that every NHS desktop has one. Every piece of A4 handover paper that we fold repeatedly until it fits into a back pocket holds reams of patient-sensitive information that we are entrusted to keep confidential.

We all know the panic of checking our pockets for the handover sheet, only to find it is empty. So why is it that, after millions invested in technology such as Electronic Patient Records (EPR), we are so loyal to this piece of A4 paper despite all of its downsides? How have we not found a replacement in 2026?

Surely Tech Can Save Us?

When the discussion arises, the obvious candidate for a handover sheet replacement involves some form of technology. Technology supposedly has an answer for everything, so why not the handover sheet?

No doctor can argue with ‘the speed of pocket retrieval’ as they pull a folded piece of paper from their scrubs. In a profession where seconds lead to greater cognitive load, the paper system acts as an external storage system for our brains. Contrast this to the experience of fighting for a free computer on wheels, logging in multiple times, and navigating through endless tabs to find the information you need. Many doctors agree that for a piece of technology to be worth their time, it needs to be accessible at all times and capable of being pulled out at a moment's notice.

We could give doctors work phones containing the necessary patient details, but could this small screen truly replace the handover sheet, which can be annotated and scribbled over at a moment’s notice? It seems the answer is no. Digital "replacements" often suffer from the fact that the vast amount of data is restricted by a tiny screen that requires constant scrolling. The handover sheet does its job effectively; it doesn’t distract you with incoming calls from the bed manager or text messages asking when you are heading for lunch. It simply reminds you of the task you intended to do when you pulled the sheet out.

Unlike tech, the sheet is also completely unstructured. We don’t have to click a dropdown or select a specific box to start typing. The friction of having to be continually precise when entering data into an EPR also slows everyone down, unlike the quick scribble on the handover sheet as you balance four tasks that need doing.

It also integrates perfectly into the handover itself. Doctors huddle around their sheets in a "campfire-esque" ring, staring at the same mental model as everyone else in the room. A power outage or dodgy internet connection could never delay such a handover once everyone has their sheets in hand.

An Eternal Relic

There is a phenomenon known as the "Lindy Effect," which suggests that the longer something has survived, the longer it is likely to survive into the future. This is intuitively correct. The longer we use a tool, the more opportunities we give its drawbacks and strengths to surface. In other words, we come to deeply understand the tool in question. If, despite all of its shortcomings, such as confidentiality risks and environmental issues, we still stand by the handover sheet, it proves our deep faith in the medium.

To replace the handover sheet would be to slow the entire hospital down; the productivity (and perhaps safety) costs would be enormous. There are few values the NHS cares about more than confidentiality, and it is a testament to the power of the handover sheet that it has endured despite these inherent security risks to patient data.

A round-up of what’s on doctors minds

“The 2025 ONS data tells us that the average rent in the UK is increasing 5.5% year on year, with this figure reaching 9% in some regions of the country, such as the North East. Every year, it seems like our salaries afford us less.”

“The first thing I do when I order imaging is to check who’s reported it. Shamelessly, I will admit that my next action depends on the name (and often the title) I find at the bottom of the report. If it’s not as I hoped, I am already on the phone to get a second opinion from my Radiology colleagues.”

“The hyponatraemia flowchart and I are best friends. No matter how many times I look at it, it will come out when I encounter a hyponatraemia patient.”

What’s on your mind? Email us!

Some things to review when you’re off the ward…

The BMA reported to the media that they calculated that 65% of its members participated in the latest and 14th round of strike action since March 2023. Here is the full piece by the BBC as doctors return to work, as negotiations between the BMA and the government continue.

The Guardian recently covered a piece highlighting the lack of stroke specialists in the NHS and how it is leading to poor outcomes in the NHS. Just 46.5% of stroke patients were admitted to a specialist unit within four hours of hospital arrival last year. This is down nearly 10 percentage points compared to a decade ago.

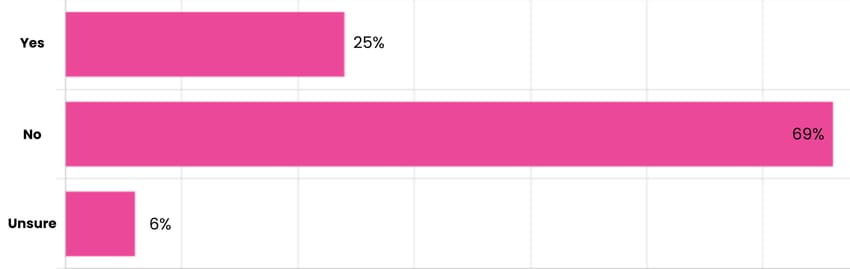

Weekly Poll

All other things being equal, would you be happy working a routine 80+ hour workweek in exchange for higher USA-levels of pay? |

Last week’s poll:

Would you be in favour of a 4-year mandatory minimum service in the NHS for UK graduates?

…and whilst you’re here, can we please take a quick history from you?

Something you’d like to know in our next poll? Let us know!

Occam’s Razor: Are Simple Explanations Failing Our Patients?

To be a doctor is to be a problem-solver. To do that effectively, we often rely on a set of principles to guide us through complex explanations of the patient’s symptoms.

Occam’s Razor is perhaps our most famous principle in logic. It suggests that when faced with competing explanations for the same phenomenon, the simplest one (or the one that makes the fewest assumptions) is usually the most likely to be true. It’s the ‘rule of thumb’ telling us that every additional assumption decreases the probability of a theory being correct.

We use this principle in medicine every day. A GP seeing her first patient of the morning, a young man with an awful headache, rightly considers a viral cause before a brain tumour. But while we hunt for that ‘simple’ unifying diagnosis, a recent paper in the American Journal of Medicine reminds us that in an era of ageing populations and polymorbidity, biology is rarely elegant. It’s a mess.

Evidence suggests that our desire for a ‘theory of everything’, to use some Hawking-esque terminology, actually leads to significant underdiagnosis. The data showed that patients with an established chronic disease are 30–60% less likely to be treated for a second, unrelated condition than matched controls. Essentially, once we see a primary diagnosis, our ‘diagnostic search’ shuts down. We stop looking because we think we’ve already ‘solved’ the patient.

The paper offers a necessary antidote by swapping William of Occam for John Hickam, who famously remarked: “A patient can have as many diagnoses as he darn well pleases.” It doesn’t quite roll off the tongue as nicely though, does it?

Help us build a community for doctors like you.

Subscribe & Share On-Call News with a friend or colleague!

Reply