- On-Call News

- Posts

- How Power Impacts Clinical Decision-Making

How Power Impacts Clinical Decision-Making

Why certainty and authority can be seductive (but dangerous) when it comes to clinical care.

Contents (reading time: 7 minutes)

How Power Impacts Clinical Decision-Making

Weekly Prescription

The Lead Time Bias: Why Early Detection Doesn’t Always Equal Better Survival

Board Round

Referrals

Weekly Poll

Stat Note

How Power Impacts Clinical Decision-Making

Why certainty and authority can be seductive (but dangerous) when it comes to clinical care.

You’ve been on the phone with the cardiology registrar for ten minutes now. Your forearm aches from holding the phone to your ear. The patient in question is in bay four and is complaining of chest pain, and what began as a clinical discussion has evolved into something far greater: a negotiation over reasoning, risk, and responsibility.

Medicine is often described as a rational discipline, built on evidence and logic. Yet even among intelligent, well-intentioned doctors, we all know that decision-making rarely involves purely rational arguments. The forces that shape our judgement (authority, confidence, hierarchy, and emotion) may often go unnoticed but they remain powerful. How many times have you stopped to dwell on them? Fortunately, the On-Call team has you covered here.

Confidence and Competence

We all know the colleague who radiates certainty. However annoying they may be, their confidence can be reassuring, particularly in high-stakes environments. Psychologists such as Daniel Kahneman have shown that humans prefer confident narratives over uncertain truths; it’s cognitively easier to process conviction than probability.

The issue is that our job deals in probabilities. Certainty is almost always illusory and can end up masking overreach. Should you always ignore confidence? Of course not. It is often correlated with expertise, but it needs to come alongside clear reasoning. It can never be a replacement for that reasoning.

The Weight of Authority

Few professions are as hierarchical as medicine. The profession may not be as hierarchal as it used to be, but for the moment anyway, titles and roles still carry significant weight. Because of this, the “appeal to authority” remains one of our most common cognitive shortcuts. When a consultant or specialty registrar insists that an investigation is ‘absolutely essential’, it is tempting to concede and request it without any further thought. After all, expertise should carry weight.

We need to be careful. Dismissing authority is not rational either, because in an efficient healthcare system, the hierarchy has to mean something. Those at the top must have jumped through the hoops of knowledge and competence to get there. But whilst the likelihood of a consultant knowing what they are talking about is higher than that of the Registrar, being top of the hierarchy is still not synonymous with accuracy.

In fact, the best NHS doctors question arguments, not just individuals. They spend more time critiquing their own reasoning than any other person and invite this questioning from others. They aren’t afraid to receive questions, because they trust the foundations of their medical knowledge to be able to give an answer. Hostility to questioning is often a tell-tale sign that someone’s foundational knowledge is on shaky ground (or they haven’t had their morning coffee).

The Gentle Trap of Flattery

Who doesn’t love a compliment? Whether it’s your shoes, perfume, or your clinical manner, these are the comments we think about at the dinner table. Flattery has surprising power in professional life. A colleague who praises your clinical insight may earn more influence than they intend. Compliments can disarm scepticism, leading us to accept opinions that deserve more scrutiny.

Emotional appeals function similarly. Fear (“What if it’s a missed PE?”), compassion (“We owe it to this patient to do everything”), and belonging (“The team usually does it this way”) can all distort risk–benefit reasoning. These motives are not malign—they stem from care, conscientiousness, and collegiality—but without awareness, they can drive over-investigation, overtreatment, or unbalanced decisions.

Recognising these emotional undercurrents is not cynicism; it is clinical maturity. Emotional awareness, when paired with reflective practice, protects both patients and professionals from decisions driven by unexamined persuasion.

Medicine is a social discipline, and that means power and influence will always be a part of it. The best doctors must understand this and use it to ensure that sound judgement still guides their reasoning.

Does The Data Really Suggest That UK Doctors Are Moving Abroad?

A good game of NHS bingo has to involve the words ‘Australia’ or ‘New Zealand’. The idea that doctors are fleeing the NHS can become so familiar, we hear it everywhere we turn. The GMC’s 2024 workforce report seemed to support such a gloomy picture by stating that a third of doctors were considering leaving medicine in the UK altogether.

But how much truth is there to the claim that the NHS is experiencing a mass exodus? Are doctors actually leaving at unprecedented rates, or are these concerns being amplified by a sense of collective frustration in the profession?

One clever proxy to judge this is a Certificate of Good Standing (CGS). This is a document issued by the GMC that confirms the GMC has no issues with you and you haven’t been going around doing rogue things and causing havoc on NHS wards.

Other regulators (for example, in Australia) require this before allowing a doctor to register. They are also only valid for three months, so can act as a short-term signal of intent if a doctor requests one.

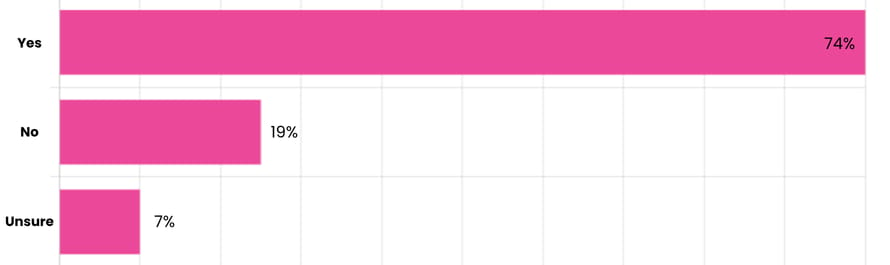

Recent data shared by the BMJ showed that the proportion of doctors who were issued a CGS but still held a UK license to practice a few weeks later had actually increased. In 2019, 53% of doctors who obtained a CGS in July were still licensed in August. By 2025, that figure was 74%. In other words, most doctors who requested one hadn’t actually left. It may be true, therefore, that more doctors appear to be thinking about leaving, but fewer are following through.

Perhaps some doctors are testing the waters and getting the paperwork ready, then deciding to stay. Or maybe they leave for a few months and decide they miss the NHS so much they want to return.

Time to start thinking about your portfolio?

➡️ Need to develop your teaching skills?

➡️ Need to demonstrate your leadership capabilities?

➡️ Need to boost your portfolio ahead of interview season?

Perhaps Medset’s Train the Trainers and Leadership & Management courses might be the answers you were looking for…

Online and Live Virtual Classroom options available - use code ONCALL10 for a 10% discount.

Need points for your specialty application?

Read this guide on scoring points for specialty applications.

The Lead Time Bias:

Why Early Detection Doesn’t Always Equal Better Survival

Why "catching it early" isn't always the cure we think it is

Anyone who has ever given a cancer diagnosis knows there are few words in medicine that carry the same weight. People often avoid saying it outright, as if the word itself had power, a kind of medical Voldemort.

This explains the widespread desire to “catch it early.” The logic feels simple: the sooner you detect cancer, the better your chances of survival. For many people, early detection means saving lives.

Whilst this belief may feel compelling, it is far too simplistic. Not all cancers behave the same way, and not all screening tests are equally useful or reliable. Some cancers are slow-growing and may never threaten life; others are aggressive and progress too rapidly for early detection to make a difference.

The Prostate Problem

Calls for a national prostate cancer screening programme have grown louder, championed by figures like Rishi Sunak and Olympic cyclist Sir Chris Hoy, who has spoken openly about his diagnosis. The Times devoted a large piece to prostate screening last week, drawing more attention to the issue.

In the UK, men over 50 can request a PSA (prostate-specific antigen) test after a conversation with their GP about the pros and cons. But there is still no national screening programme, because the evidence remains ambiguous.

The PSA test measures a protein produced by the prostate. High levels can indicate cancer — but they can also rise due to benign conditions such as infection or enlargement. As a result, many men are told they might have cancer when they don’t. Some undergo biopsies, which carry their own risks; others proceed to surgery or radiotherapy, which can cause long-term side effects such as erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

Prof Michael Baum of UCL, wrote back to The Times citing his role on the international advisory committee of the PSA test for prostate cancer trial. He referred to a trial that was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, which included over 15 years of follow-up. The trial found that for every 1000 men invited for a screening PSA test, one fewer died of prostate cancer, but the overall death levels in both groups were the same.

Many of those having the PSA test were overdiagnosed due to false positives. Many of which had their quality of life impaired by infection from prostate biopsy, urinary incontinence and impotence.

The Lead Time Bias

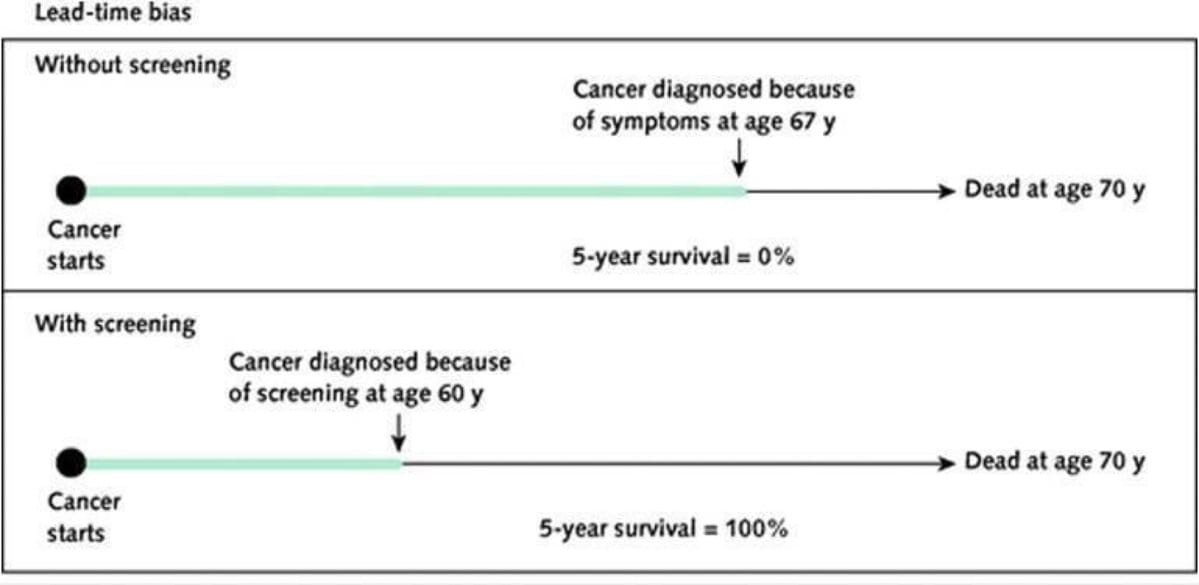

One of the reasons people — and even policymakers — overestimate the value of screening is lead-time bias.

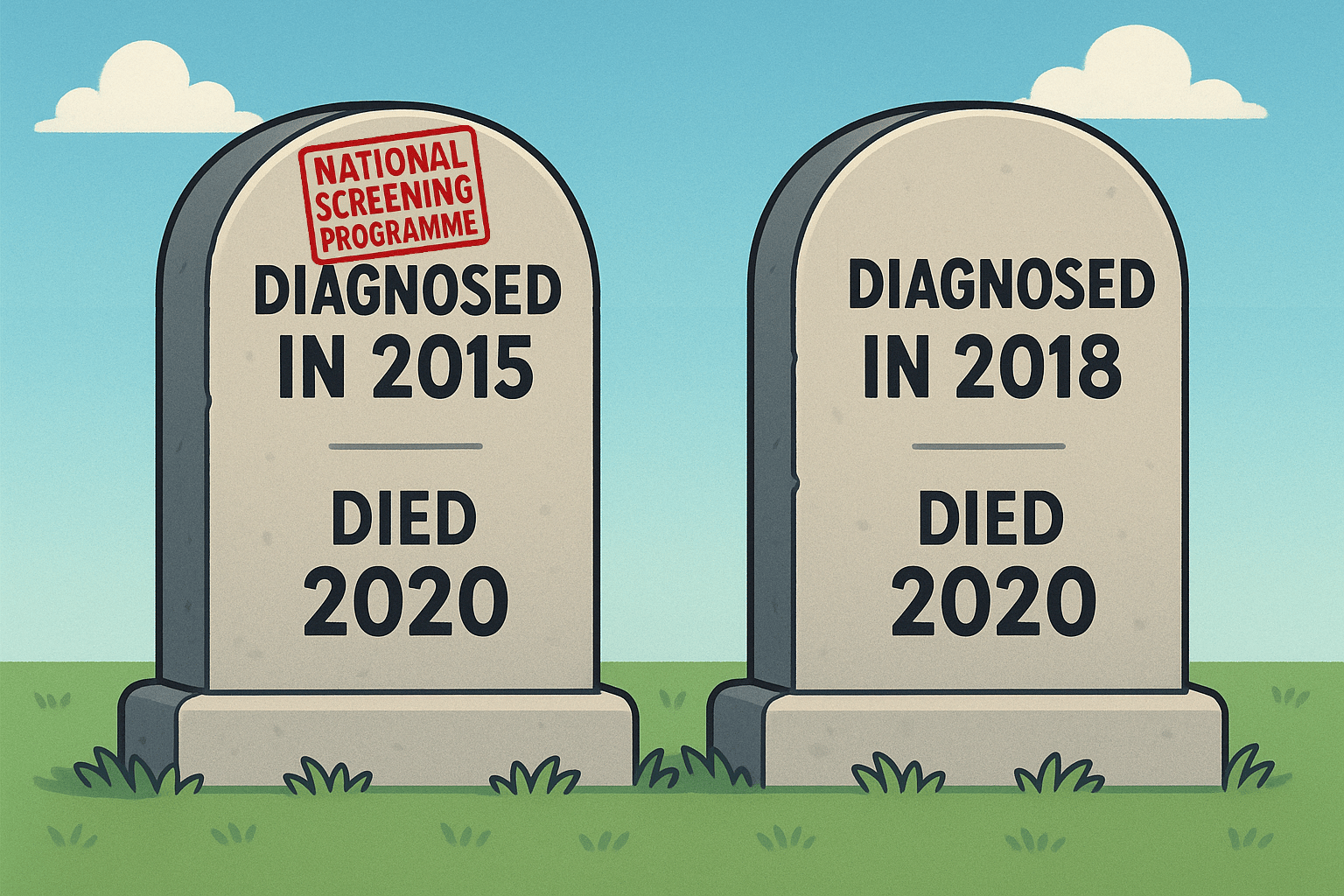

Imagine two people develop the same cancer. One’s tumour is discovered through screening in 2015; the other’s is found after symptoms appear in 2018. Both die in 2020. The first person’s “survival time after diagnosis” is five years; the second’s is two. On paper, the screened patient “lived longer.” But in reality, both lived the same amount of time — screening just started the clock earlier.

This is why many studies boasting “improved five-year survival rates” can be misleading. The only question that really matters is whether screening reduces the number of people who die of cancer overall — not how long they live after diagnosis (see below).

McCartney, M. [@mgtmccartney]. (2025, Oct 14). X. https://x.com/mgtmccartney/status/1978086752121221215

PSA + MRI Approach: A Smarter Middle Ground

The low specificity of PSA screening alone, and the overtreatment that it brings should be well known by now. The answer for some is to bring in MRI before patients are sent straight to biopsy. Trials such as the PRECISION and PROMIS trial in 2018 and 2017 respectively showed that MRI before biopsy may reduce the necessity for biopsy in 28% of men and MRI has a 91% sensitivity for clinically significant prostate cancer.

PSA + MRI may therefore ensure fewer men undergo unnecessary biopsies, but this approach also isn’t flawless, and would lead to an exponential increase in MRI demand. The same questions raised above surrounding mortality also apply, and we still await large population studies showing that this investigation reduces prostate-related mortality.

A round-up of what’s on doctors minds

“In my opinion there is nothing more egregious and damaging to our profession than those doctors who bash other specialities in-front of patients. This especially applies to general practice. Joke or not, you best believe patients will use you in their latest anecdote when discussing that speciality in the future.”

#“And the contenders for this year’s competition of phrases most associated with radiology are: ‘Stop, new line,’ ‘No acute intracranial abnormality noted,’ and ‘otherwise unremarkable’.”

“92% of psychiatry or emergency medicine applicants, also put in at least a second application. Overall 64% placed two applications or more, up from 43% in 2024.”

“best way to win around your colleagues? Be flexible in terms of swapping your on-calls.”

What’s on your mind? Email us!

Some things to review when you’re off the ward…

Here’s one for you to share with your partners. According to a paper in Nature, during ageing, men experience a greater reduction in volume across more regions of the brain. Basically men’s brains shrink faster. Academics remain stumped, however, as the data seems to suggest that women are still more frequently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Read the full paper using the link above.

Kiwi may be the latest constipation miracle cure, according to the guys at King’s College London. The debate about whether to keep the skin on or off can rage-on if you like, but for now, just buy those Kiwis. Here’s the full article from the BBC.

Monday’s are the day to avoid in A&E if you want to sideline the busiest day. 16% of all A&E attendances came on Monday from the 2019/20 data. Here’s the full article for a breakdown of the numbers.

Weekly Poll

How likely are you to move abroad at some point in your medical career? |

Last week’s poll:

Does (or did) rotational training impact your decision to get on the property ladder?

…and whilst you’re here, can we please take a quick history from you?

Something you’d like to know in our next poll? Let us know!

So You’ve Joined The Private List - Now What About The Money?

After years of training, exams, bottlenecks and on-calls, your name badge finally says consultant. You’ve taken the first steps into private practice: found an accountant, hired a PA, launched a website and paid for indemnity that costs more than your first car. Now comes the next stage: registering with a private health insurer, like Bupa.

Doctors register with companies such as Bupa and AXA to become recognised providers. The insurer lists you in its directory, sets the fees you can charge for specific procedures, and expects you to follow its terms. Once recognised, you can see insured patients and invoice the insurer directly instead of the patient.

The catch comes when you open the insurer’s fee schedule and your heart drops. Some procedures pay so little they barely cover the time, risk and responsibility involved. Once you agree to an insurer’s schedule, that figure is the total you’ll receive. You can’t bill the patient for the difference (known as balance billing) because UK insurers don’t allow it. If Bupa’s fee for a C-section is £X, that’s exactly what you’ll be paid.

Some consultants accept this trade-off for the convenience. Others choose a different route, staying independent so they can set their own fees and bill patients directly. A bit more hassle, but potentially more rewarding for the consultant.

As always, one principle applies to everyone entering private medicine: read the fine print before you sign anything, especially in the world of health insurance.

Help us build a community for doctors like you.

Subscribe & Share On-Call News with a friend or colleague!

Reply